The story leads us to some extraordinary pieces within the archives of Nederlands Dans Theater (NDT) and maybe, more boldly speaking, within the art of dance in the post-war Dutch society. The idea of “let’s go out to the field” invites us to imagine different narratives and let ourselves be taken by the richness of our audiovisual archives. Thereto, we will present three pieces created or adapted to the screen, beginning with Hans van Manen’s own dance through the fields in Kaïn en Abel (1961).

Video recordings are an important component within the oeuvre of Hans van Manen and, moreover, appear to be running through the veins of NDT. In the early sixties, the company collaborated with the Dutch broadcaster VPRO; ensuring that even today we are able to have a glance of the company’s earliest pieces. In programmes as “Inleiding tot de dans” (“Introduction to dance”) directed by Joes Odufré, the dancers and choreographers of NDT were offered the opportunity to introduce their characteristic body language – based on both classical and modern techniques – to a large Dutch audience by presenting and explaining fragments of their repertoire.

In an interview celebrating the company’s fifth anniversary, Van Manen – at that moment artistic director – explained that the successes of NDT’s television performances were grounded in the fact that the company took its audiences serious and didn’t comply to what could be regarded as public taste: “We were free to stage the things we wanted. And precisely because we didn’t compromise, people have come to understand and love ballet.” A fascinating side note was, furthermore, that the company not only presented existent repertoire on television, but also created ballets which premiered on the screen.

Kaïn en Abel is one of those ballets. The broadcasting, commissioned by VPRO, begins with an introduction through drawings, paintings and sculptures. The story of the two brothers, in this case fighting over a woman, subsequently unfolds through movements by a few of NDT first dancers: Jaap Flier (Kaïn), Gérard Lemaître (Abel) and Hanny van Leeuwen. The ballet, however, not only reveals Van Manen’s eye for film, but also his nose for bringing together a talented set of artists: visual artists as Carel Willink and Jean Paul Vroom, and jazz pianist and composer Pim Jacobs.

The early cinematic encounters of the company turned out to be a stepping stone to a much broader involvement with the camera; most notably through the possibility of registrations. During the seventies, Hans Knill (former dancer and artistic director together with Jiří Kylián in his early days) had started to experiment with all kinds of recording systems and camera angles. Over the coming decades every ballet, rehearsal, reception or international tour would be recorded and stored into the archives. At the same time, choreographers associated with the company continued to explore the field of dance on screen; resulting in a handful of registrations and adaptations for television, as well as some films.

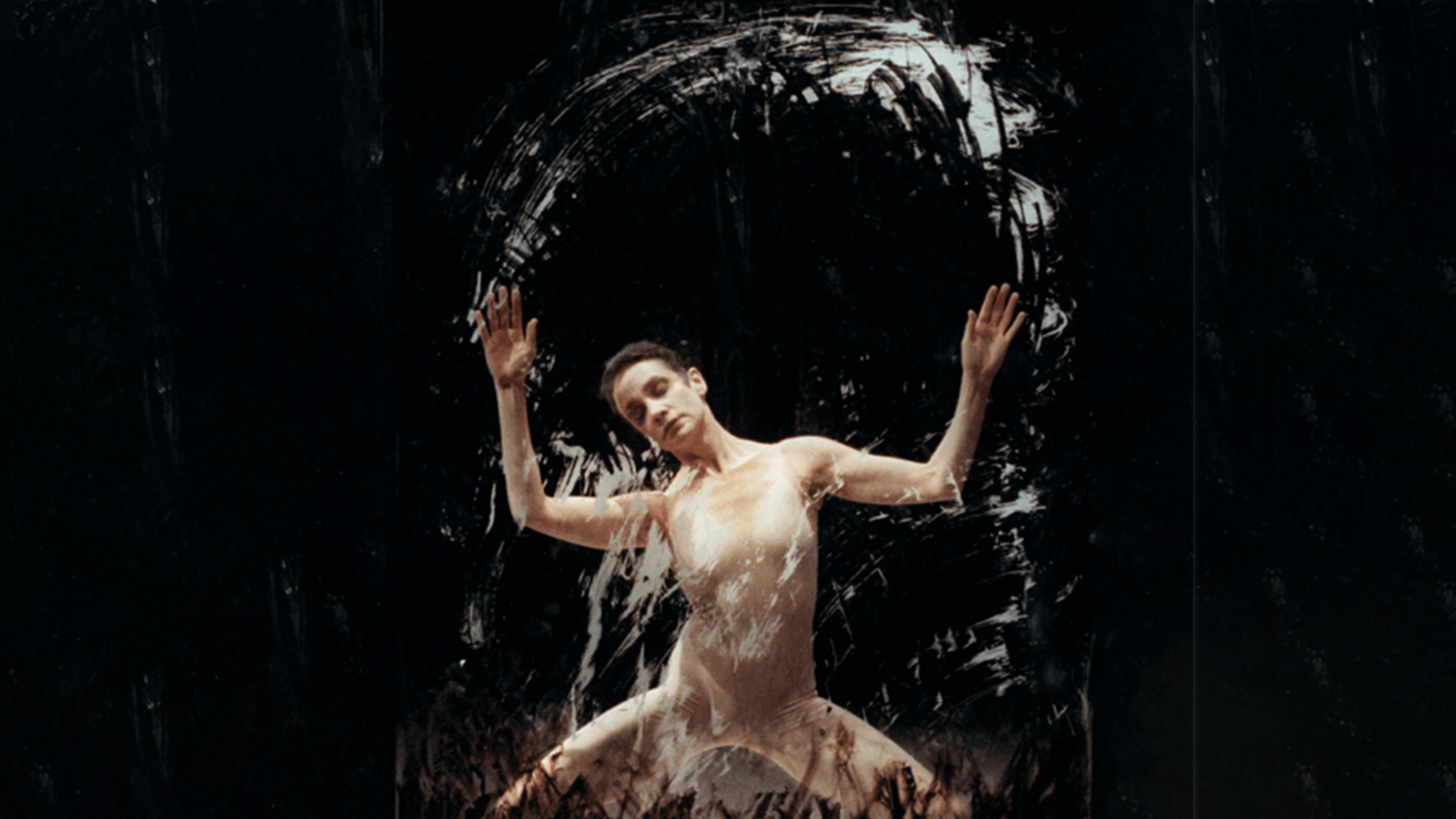

For this particular program we want to resurface the registration of Silent Cries by Jiří Kylián. A true masterpiece created in 1986 and subsequently recorded in 1987 for a co-production of NOS and RM Arts. The choreography is staged to Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (1894), conducted by Bernard Haitink and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra. While the composition was inspired by the (nearly) eponymous poem of Stéphane Mallarmé, this particular recording attests to Kylián’s own way to provide the lyrical score with a sophisticated layer of spatial expansion: dedicated and danced by Sabine Kupferberg.

For the last film, Mouvement de la Hollande, we go back in time to September 1959. The film was directed by Leen Timps and symbolically addresses the reconstruction of the Dutch society; the sense of loss, transition, and renewed experiences with art, technology and science after the Second World War. The scenes are choreographed by Rudi van Dantzig and performed by dancers of Sonia Gaskell’s Nederlands Ballet – the precursor of the Dutch National Ballet. And just by being part of this group, spinning around this figure of “Madame”, those dancers participated in some decisive moments within the art of dance in the Dutch society.

In a strange way the film functions as kind of a hinge. It was recorded at a moment that NDT did not officially exist, yet broadcasted a few weeks after the company had its first performances. By this time, a large part of the dancers in this film had become constitutive members of the first tableau of NDT, amongst which those dancing the film’s leading roles: Jaap Flier and Milly Gramberg. Some of the scenes would even end up in a small book titled Nederlands Dans Theater with photography by Ed van der Elsken and Eddy Posthuma de Boer. At the same time, the spectator witnesses the unmistakable influence of Gaskell, her intricate relationship with Van Dantzig, and maybe even a reflection of her motto “The arts are just as life, an eternal new beginning.”

These three films take you along different places, histories and choreographies – different kinds of cinematographic fields. We strongly advise you to stay in and just watch them, as you never know how a walk into the fields might end…